IMPERATO WEST AFRICAN GALLERY

Welcome! We are honored to share one of the finest collections of West African Art in the US with you. First off as a bit of trivia, not one artifact in this gallery was collected by Martin + Osa Johnson; they helped pioneer the ideology "Take a Picture, Leave Only Footsteps." The art pieces you see here have all been gifts to the museum to help lend more perspective into the varied African cultures and enhance the unprecedented Visual History collection produced by the Johnsons.

The Gallery started in 1973 with the donation of several hundred pieces by Dr. Pascal J. Imperato, then a physician and instructor at Cornell Medical University. Dr. Imperato discovered the museum just as we opened after he had made a trip to Lake Paradise in Kenya where Martin and Osa Johnson had lived for several years.

Today, Dr. Imperato is recognized as a distinguished Africanist, African art historian, and ethnographer. He is internationally respected for his studies of the Bamana, Dogon, and Peul peoples of Mali, based on field-research conducted over many years. He is also well known for his studies of the Luo of Tanzania and the colonial era history of northern Kenya. Since the opening of the West African Gallery, Dr. Imperato has continued to donated many of his finest pieces and has encouraged other Africana scholars and collectors to do so as well. Much of the text used in our exhibits and here in the descriptions come from his numerous publications.

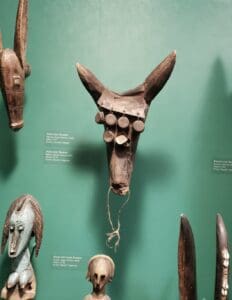

As you enter the Gallery, you will see these Bambara (Bamana) dancers who wear the headdresses of the Tyi Wara, the antelope who taught the first Bambara to farm. They dance, according to season, for planting and harvesting and for a plentiful crop.

THE WEST AFRICAN COAST

To your left as you look into this alcove, you will see the large four legged Nimba Shoulder Mask (17-24) from the Baga people. It is placed over the shoulders of the dancer who is able to see through the hole between the breasts. A grass skirt is tied below the breasts and around the waist to conceal the dancer's identity. This is used by the Simo Secret Society during ceremonies after the rice harvest.

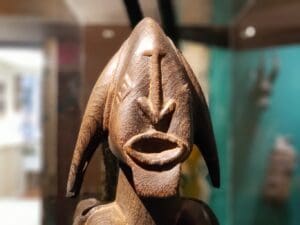

A second Baga piece is the Bird Head Ritual Object (17-257). Used in magic rituals, these figures sometimes have hidden compartments for ritual artifacts. The museum has two of these objects, but neither has secret places.

The Baule Masks (17-28 & 17-30) are of beautiful women and are used by men at agricultural ceremonies. The Mouse Oracle Box (47-6) was used for divination. The mouse was kept in the lower part of the box and was released to the upper level which had been spread with seeds. The movement of the seeds was read by the medicine man as a fortune teller would read tea leaves.

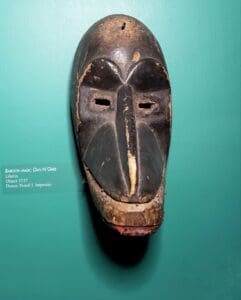

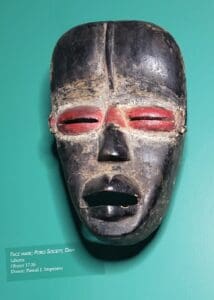

Like the Baule masks, the Dan Poro Society Face Mask (17-26) also represents a woman, known as a Dea. It was danced with during the circumcision ceremonies. The N'Gere Warthog Mask (17-25), the Dan Baboon Mask (17-27) and the Minianka Face Mask (17-45) were all used for social control. The wearer acted out behaviors disapproved of within the group.

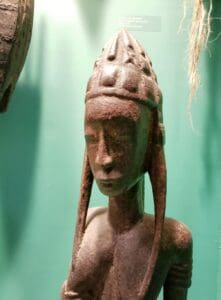

Ancestor Figures or Statues found throughout the exhibit were carved to hold the spirits of ancestors and were kept in the family shrines where they were given offerings of beer or animal blood in the belief this would cause them to be pleased and bring blessings to the petitioners.

On the final wall of this case is an Ashanti Fertility Doll (17-33) and an Ashanti Linguist Staff (48-4). The Ashanti are known for their vibrant artistic traditions, including textiles, sculpture, gold weights, as well as gold and silver jewelry.

The south case holds pieces from the Senufo people, who are noted for their strong carvings. Centered are the two Firespitter Masks (17-38 & 17-219). These masks were used for anti-witchcraft and for burials. Danced in at night, the dancers (sometimes there were 10-15 men dressed in Firespitter masks) carried tinder which was made to glow and smoke in an effort to frighten and drive the witches from the village. The Firespitter is represented as having the jaws of a crocodile, the tusks of a warthog and the horns of an antelope. Figures representing the hornbill and a chameleon are often found between the antelope horns. This mask represents a mythological being who protected the villagers from sorcerers.

The large bird (Sejen), Hornbill (17-44), is a symbol of fertility. Bird figures like this are among the many art forms associated with Poro, a society of initiated Senufo men. Poro functions as a system of governmental and economic control, preparing young men for their roles as adults. The Hornbill ‘Calao’ bird to the initiates of the Poro society is known as the ‘porpianong’ or "child of the poro" and they were kept in a sacred grove where rites took place. The Drum (17-42), one of three donated to the museum, was used for funerals and carved with the five animals considered to be the first living creatures: the crocodile, chameleon, tortoise, serpent, and hornbill.

The Senufo Face Mask (17-35) is known as Kpelie and it represents the ancestors. The mask's features, such as the stylized twin hornbill on top, represent fertility, procreation, and the mythological founder of the Senufo people, and is used in Poro Society rituals. The large Helmet Mask (17-211) is worn by senior dignitaries of the Lo Society at funeral ceremonies, death anniversary rituals, and initiations.

Besides funerals, death anniversaries were held following a burial by some time, the time for the family to save up the money for the ceremonies. Almost all of these pieces were used in the initiation ceremonies. A mask could be used for many different rituals, but the shaman was the one who knew which masks could be used for which purposes.

JEWELRY

Cases of jewelry in an African art exhibit are unusual, but are considered by the donor and the museum to be quite worthy of exhibition.

THE CASE ON THE LEFT CONTAINS JEWELRY FROM THE SAHARA & SAHEL.

Amber necklaces such as #1 (17-33) are made by the Peul nomads, but also by a number of ethnic groups in Africa.

The Straw Necklace #2 (17-135) was worn by a Maure woman. This aromatic Maure Necklace #3 (17-134) is made of small resin beads.

The Songhay (Songhoi) make jewelry from Borgus grass. It is golden and is fashioned in the same styles as gold jewelry as shown in #4 through #10 (17-137, 17-138, 17-139, 17-144, 17-142, 17-140, 17-141).

The Earrings #11 (3-51) are from the Peul tribe. They belonged to a young girl. As the family's wealth increased, they would be melted down and more gold added until the earrings were pure gold.

Stone Bracelets #14 (17-128) are carved by the Tuareg and were worn by men on the upper arm.

The Metal Ankle Bracelets #12 (17-120), #13 (17-121), #15 (17-117) and #16 (17-116) are all worn by the women.

The last three pieces are also ankle bracelets. The Copper Bracelet #17 (17-118) would have been worn by a young Dogon girl. The two Aluminum Bracelets #18 and #19 would have been worn by Maure women from Mauritania.

THE RIGHT CASE CONTAINS JEWELRY FROM THE SAVANNA.

There are four necklaces, three from the Bambara which are made from blue and white Venetian glass # 1 (17-132), white beads and large seeds #3 (17-129) and carved from a madia root #2 (17-136). The fourth necklace #4 (17-30) is from the Malinke and is made up of Venetian trade beads.

The Ankle Bracelets (17-126 and 17-127) were made by a Dogon blacksmith, #5 for a young woman and #6 for a young girl.

The Belt of Cowrie Shells #7 (17-131) is made of a shell which is used all over Africa and in the oceanic areas where it was found. The museum has a warrior's "apron" from north eastern India featuring the same shell.

The large Ankle Bracelet #13 (36-1) was a gift to the museum by Alice Cobble, a missionary in the Belgian Congo. It was said to be worn by the chief's favorite wife. It weighs over six pounds.

Four of the Arm Bracelets #8 (31-3), #9 (31-2), #10 (30-3) and #11 (30-2) were given to the museum by Malian co-workers of Dr. Imperato, Mr. Keita and Mr. Sanogo. These bracelets are made of leather or plastic strips.

The remainder of the jewelry in the Savanna case are also arm bracelets. They are composed of metal #12(17-119), #14 (17-125), #15 (17-122), #16 (17-123) and were worn by girls and young women and probably made by a blacksmith. The last bracelet #17 (17-24) is made of iron and copper and was worn by an older Dogon woman.

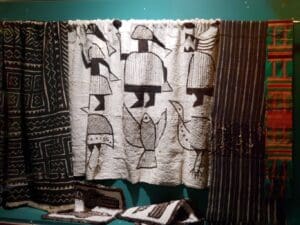

TEXTILES

The Kente Cloth #1 and #5 (3-60 a and b) exhibited at either end was usually designed and made by men. The pattern was not recorded in earlier days. It was said that the ruler of the group had first choice, the weaver had only second choice. This came from Ghana.

The second piece is called Mud Cloth #2 (17-186), made by the Bambara, in Mali. It is called Bokolanfini and the process uses bark and leaves, aged mud, a lye soap as mordant, sun drying and finally beating the mud out and rinsing.

Korhogo Cloth #3 (17-191) is also made with a mud process. This was made by the Senufo people of the Ivory Coast.

This Hand Woven Strip #4 is unidentified.

The Handwoven Mats #6 (3-66) were made in Ethiopia. The design is woven in the mat.

NIGERIA & CENTRAL AFRICA

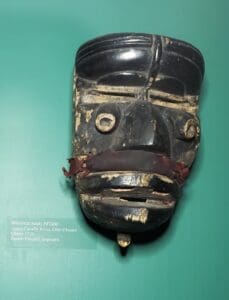

On your left in this alcove, seven of the ten masks are from Zaire, the Republic of the Congo, and Cameroon. The remaining three are from Nigeria.

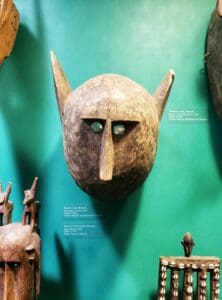

The two masks from the Pende people (29-1 and 29-3) are used during the initiation and the circumcision ceremonies for the age group of boys ready to prepare for manhood. The Bayaka Mask (17-113) was used by a boy after his bush school training which ended with circumcision. He and his age-set companions from the nearby villages would wear their masks when they went to dance in celebration of their newly acquired manhood.

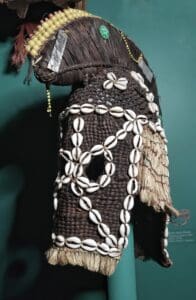

The Beaded Skirt (3-160) was purchased by the museum. It is a dancer's skirt from Nigeria, but we do not know its tribal origin.

The Bateke Mask (64-1) is famous for its connections with Picasso. It is written that this was the particular style of the mask that influenced the style of that famous artist. We are not entirely sure of its use.

The Bamun Mask (39-2) is from Cameroon and is carved in the well known style of the Bamun. It was used for new moon ceremonies.

The Kongo Stone Funerary Figures (29-4 and 29-5) would have been privately owned and kept in a family shrine.

The Ogoni people are closely related to the Ibibio people of Nigeria. We have no information on the use of their mask (48-2).

The Yoruba Shrine Guardian Post (46-2) is one of a pair in our collection. Its name explains its use.

The end center case is filled with masks from Nigeria. Except for the Wurkun Crop Guardian (47-4) and the Urhobo Shrine Figure (41-1) [mislabeled Yoruba] the rest are attributed to the Yoruba people.

The Yoruba have a rich mythology and an assembly of gods, called orishas, numbering around 600. The orisha of twins is Ibeji and the Twin Figures (45-2 and 47-5) are also called Ibeji. The orisha of lightning is Shango and the Dance Wand (17-108) is used in his name, also called the Thunder God. The Donor was unsure of the provenance of the Mask (44-2), but said it was possibly for the Egungun society which dances for the ancestor cult of the Yoruba.

The Crop Guardian Figure (47-4) is inserted into the ground to protect the growing crops.

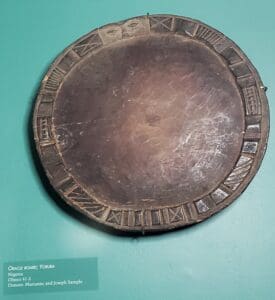

The wooden disc is an Ifa Divination Board (41-3) on which the diviner spread a white powder and then traced the message with his finger. The large Bowl (45-1) was used as a storage place for the palm nuts the diviner used in his work.

The Urhobo Shrine Figure (47-1), which is mislabeled as coming from the Yoruba people, is the spirit of a mythical warrior and represents one of the forces of nature.

The Gelede Society Masks (42-1, 39-1 & 17-106) celebrated the god of the earth and fertility at the yearly fertility celebrations and at the funeral of a member of this secret society. The Gelede Society is known for its unique cap masks.

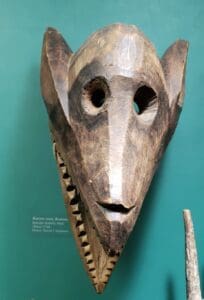

On your right, the next case is dominated by the skin covered Ibo Crocodile Cap Mask (47-2). Used for agricultural rituals, the crocodile is probably a totem figure, and the coils are an imitation of the hairstyle of the tribal women.

All of the figures in this case are also from Nigeria, and all but the Mumuye are from Southern Nigeria. The Mumuye Standing Figure (40-3) is an ancestor figure.

The Ijaw (Ijo) are fishermen, swimmers and boatmen so it is not surprising that their Mask (47-3) would be of the water spirit cult.

The Ibo, with the Hausa and Yoruba, comprise over half of the population. The British made the three groups into political units in Nigeria with each of the three groups in charge of a section of the country. The Ibo were a less successful group under this system because they were not unified into one tribal group. So there are many divisions of the Ibo and cultural contrasts between them.

The Seated Ibo Figure (42-2) is a personal possession which brings good fortune to a young man who has just left his parents' home. The figure stays with him and is destroyed when he dies. The Ibo Ancestor Figure (17-110) is kept in a family shrine and presented with prayers, offerings, and sacrifices at intervals.

The Helmet Mask (40-1) honored the dead ancestors and enforced social control. The Ibo Mask (17-111) is used to mimic the activities of daily life using the pantomimes as social control. The Ibo Maiden Spirit Cap Mask (39-3) was used by the men's mmwo society to represent a variety of spirits.

The Ibibio Mask (43-1) of the Ekpo male society honors dead ancestors and enforces the law. The Ibibio Face Mask (48-1) has an open mouth and teeth of twigs. Its use is not known by the museum. If you have information on this mask or any object in our collection, please share it with staff so we can update our archives and artifact origins.

THE SAHARA AND THE SAHEL

Upon entering this alcove, your attention will be drawn to the Cotton Blanket (17-185) on your right. It was woven in four inch strips which were sewn together on a sewing machine with a zig zag stitch. There are embroidered designs and a short fringe on either end. This was made by the Peul people who are also known as the Fulani. They are farmers and merchants as well as pastoral nomads.

The attention-getter in the other case is the Camel Saddle (17-19) made by the blacksmith caste of the Tuareg. The rider sits on the seat and crosses his legs in front of the saddle, resting his feet on the camel's neck. The Tuareg men wear veils; the woman do not. They have been called the "Blue Men of the Sahara" since the indigo dye used in their garments wears off on their bodies. They are Berber people, primarily camel nomads.

The Straw Hats are Peul (17-179) and Songhay (17-17). The Songhay (Songhoi) are Islamized people who live along the banks of the Niger River. They are sedentary, keeping herds of goats, camels, and cattle.

The Knives with Scabbards (17-2, 17-3, 17-4 & 17-5) were all made by the Tuareg.

There are three Tuareg Swords with Scabbards (17-11, 17-180 & 17-12) and a Tuareg Metal Spear (17-267). The Peul Sword (17-9) has a slightly curved blade with a leather scabbard.

The Maure Leather Bag (17-226) is the bottom two-thirds of a kid (small goat). After tanning the leather and patching the natural openings, a closure is added at the top and it becomes a water carrier. The Maure are known also as Moors and Bedouin Arabs.

The Songhay Leather Wallet (17-7) hangs around a man's neck, for if one wears a robe, there are no pockets for money. These people are also sedentary.

Two Saddle Bags are exhibited, one from the Tuareg (17-15) and one from the Peul (17-233). They are both used for camels.

The Tuareg have carved a Wooden Cup (17-18), made a Tobacco Pouch (17-231) and a small Brass Container (3-71) which would probably hold a saying from the Koran and be worn by a man.

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

All of these instruments are made from natural materials.

The Folk Lute (3-55) at the right of the case was made by the Peul from a carved wooden base with a skin pegged to the top of the wooden base. The lute is stringed as a guitar would be. It was purchased by the museum.

The Shofar Horn in the center of the case was made from a hollowed out Greater Kudu Horn. A visitor noticed this piece and after returning home, donated the full Kudu head we have on display on the 2nd floor. They wanted future museum visitors to see more of the amazing animal and know that when an animal is taken for food, nothing is wasted.

THE REST OF THE INSTRUMENTS ARE DRUMS:

Dogon Talking Drum (17-103) from Mali. It is placed under the arm. Tones can be altered by squeezing the drum between the arm and the chest. A tribal drummer can make the drum understandable to his people by imitating their language.

Bambara Drum (30-4) is called a Jembe. It is sculpted from one log and played by placing the narrow portion between the legs and drumming. It has a high resonance.

The remaining two drums are Bambara (17-225 and 17-199). They are made from calabash gourds, covered with cowhide and tied with ropes and an iron ring and used by age-set associations.

An "age-set association" starts as a group of adolescent boys enter the initiation process together (a group every 5 or 6 years). The age group will remain together as initiates, warriors, junior elders, and senior elders. In the Bambara tribe, initiation lasted 6 years.

Door Locks

The museum has a fine collection of wooden doorlocks, including a built-in doorlock on a Dogon Granary Door (17-102). The figures are sculptured nommo, the mythical ancestors of the Dogon. The door would have been placed in the small opening in the side of a tall mud storage edifice as seen in the photo mural on the wall of the Sahara display. The Bambara and Dogon use this type of door lock. The Dogon designs are usually simpler, and they use fewer house locks than the Bambara do.

THE SAVANNAH

Across the room, on the right of the doorway to the Tyi Wara dancers you will find:

The Bambara Hyena Masks (17-77, 17-163, 17-283, 17-309, 17-76, and 17-169) are used by the Kore Society, the highest grade initiation a man could attain. Kore's purpose was to restore the man to harmony of spirit he had enjoyed prior to his circumcision (when he was a boy), to join him to God and to help him triumph over death. The masks could also be used for entertainment of the age set associations and for the Society of the Tyi Wara.

The Bambara Baboon Masks (17-66 and 17-280) are used by the age set associations and usually danced at night so the dancer's identity could be better hidden from the women and children. Known as Zantebega, the name translates as "he with the large paws."

The Bambara Buffalo Mask (17-67) is known as Sigi Koun (Sigi must mean "buffalo" because koun means "mask"). This mask is used for entertainment of the age set associations.

As stated earlier, an age set association starts as a group of adolescent boys enter the initiation process together (a group every 5 or 6 years). The age group will remain together as initiates, warriors, junior elders, and senior elders. In the Bambara tribe, initiation lasted 6 years.

The Bambara N'Tomo Society has six levels. The N'Tomo Masks (17-68, 17-69, 17-71, 17-72, 17-74, 17-149, 17-173) may indicate the level by the number of columns or horns:

Two horns symbolizes that man is both man and animal.

Three horns symbolizes that man is spirit, masculinity, impulsiveness, and desire.

Four horns symbolizes that man has masculinity and femininity.

Five horns symbolizes that man must work to live.

Six horns symbolizes that man has six senses.

Eight horns symbolizes man's ultimate level of knowledge and recognition of his mortality.

The Bambara Dyofaga Theatrical Mask (17-308) is used for pantomimes within the Dyo society. We have no further information.

The Bambara Circumcision Rattle (17-82) is carried by the newly circumcised boys and as they walk around and sing, it is rattled. The rattle, Wassamba, symbolizes man as he is born into the world, complete but ignorant.

The Heddle Pulley (17-84) is carved by the blacksmith at the request of the weaver. The figures can be animal totems or ancestor spirit representations.

The Bambara Horseheads (30-1 and 17-65) are used by the Kore and Dyo societies and also by age set associations. #30-1 was used as a stick horse by the Kore Dugaw, the buffoon for the society.

The Bambara Marionette Figures and Heads (17-86, 17-207, 17-215, 17-216, 17-298, 17-85) are used for masquerades and pantomimes. They represent women. The puppets are danced with by the age set associations with the dancers camouflaged under cloth covered frames.

The Bambara honor twins and have a twin cult. When a twin dies the blacksmith carves a Small Figure (17-88) and the spirit of the dead twin is thought to live therein. The mother cares for the live twin and the carving as if they both were alive.

This Grandusu is a Bambara Maternity Figure (17-87) and would be the center of a fertility cult of the same name.

Continuing around the corner on the south side of the room is a Bambara Gouantigui Horseman Figure (17-299). He came from the same shrine as the Maternity Figure (17-87). The patina that covers them is from offerings of blood or beer. He symbolizes the divine blacksmith.

The next group are of Tyi Wara (Chi Wara), Bambara Headdresses (17-299, 17-61, 17-64, 17-150, 17-174, 17-243, 17-256, 17-264, 17-310). These antelope masks are used for agricultural rites, entertainment and social control. Two other Antelope Headdresses (17-62 and 17-63) are from the Wasalunke who are closely related to the Bambara.

At present a Bobo Fing Helmet Mask (17-346) is being shown in this case.

Crossing to the west wall, the Dogon Kanaga Masks (17-98 and 17-99) draw one's eye. Their cross like superstructure represents a bird, the lesser bustard. They represent both the male and the female and are used in death anniversary ceremonies when there might be 40 dancers wearing the Kanagas.

The Dogon Cloth Mask (17-94) represents a woman of the neighboring nomad Peul Tribe and the way she would have worn her hair. It is used by the Awa society members during funeral, death anniversary, and agricultural ceremonies.

The Dogon Antelope Masks (17-96, 17-222 and 17-300) represent the roan antelope and are used by the Awa society.

The Dogon Rabbit Mask (17-97) is one of 78 different masks used by the men of the Awa society during funerals, death anniversaries and agricultural rites. The animal masks represent ancestors through the use of their clan totems.

The Weavers Pulley (17-154) would be owned by the individual weaver, not a secret society as in the case of the masks. The Dance Wand (17-183) was used for ceremonies of the Sigui Dogon group. The Dogon Ritual Staff (17-278) is used by healers or cult leaders.

The bronze-covered Marka Face Mask (17-46) represents a beautiful woman and is used during masquerade performances by age set associations. The dancer mimics a young woman.

The Malinke people, closely related to the Bambara, also have a N'Tomo Society and N'Tomo masks, some of which are covered with aluminum (17-75) and some which are not.

The Malinke Game Board (17-177) called wori, among its many names, belongs to the family name of Mankala. Within the tribe, it was played only by the men.

The Malinke Stool (17-48) was used by adults in everyday living. It would have been carved by the blacksmith from a single log.

The Kurumba Antelope Headdress (17-56) was used for agricultural ceremonies and after the period of mourning at a ceremony to disperse the spirits of the dead from the village.

The Mossi Wango Society Mask (17-292) was is used in funeral ceremonies and during harvest festivals. The Mossi have been politically dominant in their Upper Volta area since the 14th century.

The north case holds masks from the Bobo peoples. Having nothing to do with skin color or color of their garments, the Bobo are named the Black Bobo (Bobo Fing), the White Bobo (Bobo) and the Red Bobo (Bobo Ule). All three are represented in our collection, and pieces from the Bobo Fing and Bobo Ule are on display in this exhibit.

The Bobo-Ule Do Society Mask (17-312) was probably used in the society's agricultural rites and funeral ceremonies.

The Bobo Fing Owl Mask (17-58) was also used by the Do Society. The dancer was first covered with a camouflage of dark brown raffia, and he held the mask over his face with the handle under the chin.

The Bobo-Ule Stool (17-53) was called nani and was used by an adult. Most of the everyday articles sculpted from wood were called nani.

The Bobo Fing Buffalo Mask (17-57) was danced with by Do Society members (the strong ones) for agricultural festivals, funeral ceremonies and rituals to purify the village. This style is rare.

The Bobo Buffalo Head Mask (17-210) is used for the same ceremonies as are the Bobo Fing (17-57) and the Bobo-Ule (17-209) Buffalo Masks.

The Bobo Fing Antelope Mask (17-175) is also a part of the Do Society and is used for similar ceremonies.

The eyecatching artifact in the center case is the brightly colored Bozo Antelope Head (17-49), a puppet. It is used in age set association masquerades. The lower jaw can be manipulated. The Bozo people are river people, fisherman on the middle Niger.

The Bambara Ritual Statue (17-89) was used by the Dyo Secret Society. Called Dyonenyi, it was carried by the N'Tokofa, who are buffoons during their annual rites.

The Dogon Drum (17-263) is carved with three rows of figures. We do not know if this drum is designated for special ceremonies.

The remaining figures in this case are Dogon Ancestor Figures. The two larger figures (17-100 and 17-101) are younger and have had better care. They show the patina caused by the gift of annual sacrificial offerings of blood and gruel in order to implore the ancestor spirits for help.

The smaller ancestor figures (17-317, 17-318, 17-319, 17-320, 17-321, 17-322, 17-323, 17-324) are, as are the larger figures, made for family or village shrines. They were petitioned for protection, fertility of the soil, and well-being.

The Dogon of the Bandiagara District of Mali were known to place old and unused ceremonial carvings in the caves of the cliffs behind their homes.

As you exit the gallery, be sure to look up the stairs to the 2nd floor exhibits to see three masks that should be on display here, but cannot due to their height.

Halfway up the stairs, are two Dogon Sirige Face Masks (17-104 and 17-105). They represent many storied houses. They play an important part in funeral and death anniversary ceremonies. As with all the wooden Dogon Masks, the dancer clenches a horizontal bar on the inside of the mask between his teeth in order to keep it in place. The mask is also tied around the back of the head with cords. The dancer does not use his hands to support the mask, but he bends back and forward, touching the tip of the mask to the ground and spinning the mask in a horizontal position. The Great Mask (17-311), sometimes as long as 30 feet, is used every 60 years for the Sigi festival. Called the "Mother Mask", it is venerated as the mother of all the masks. Usually a new mother mask is made every 60 years. It is carried, not worn.

All three masks are approx. 15 feet tall and this was the only space in the Santa Fe Depot that would accommodate them being exhibited upright. The view from the 2nd floor is more impressive. There is elevator access in the lobby.